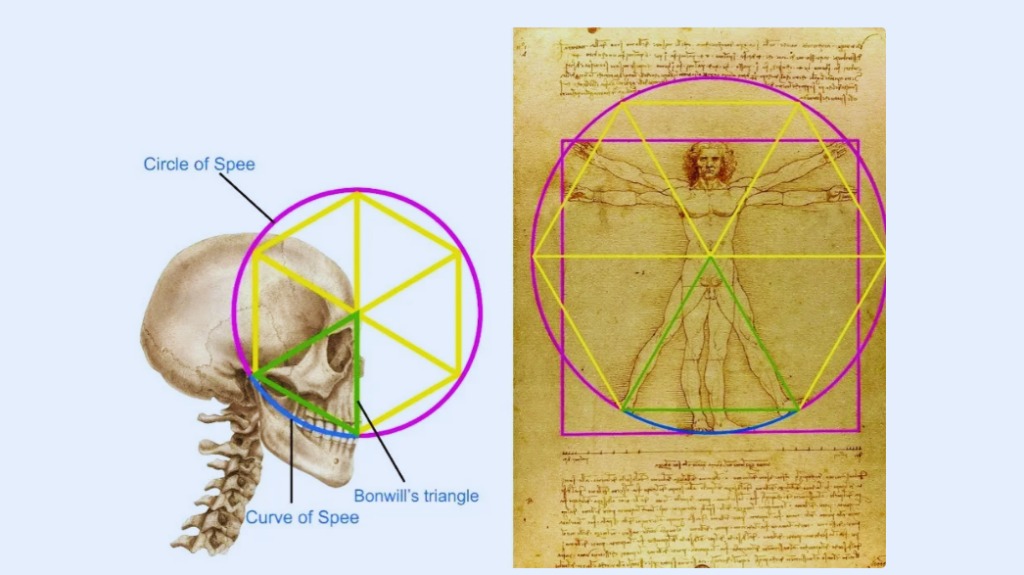

Drawing on his interdisciplinary work in dental anatomy, geometry and human evolution, London-based dental surgeon Dr. Rory Mac Sweeney has proposed a new interpretation of the geometry behind Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man.

Historians and mathematicians have long debated the meaning of the famous sketch, including why da Vinci drew the man inside both a circle and a square—shapes whose centres do not align.

The 15th-century polymath, considered one of the most brilliant minds of the Renaissance, based his proportions on the work of the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius, who wrote that a man’s height should equal his arm span, among other ratios. However, da Vinci subtly altered the figure to fit both shapes, making it more anatomically and visually pleasing.

In a paper recently published in the Journal of Mathematics and the Arts, Mac Sweeney identifies a hidden equilateral triangle embedded within the Vitruvian Man—a geometric feature he says is key to understanding the drawing’s deeper structure and may help crack a 500-year-old mystery.

“Leonardo’s drawing isn’t just a study in proportion—it’s a map of tension.” Mac Sweeney.

Read related article: Forensic Dentist Uses Experiences Decoding Murder Evidence As Inspiration For First Crime Novel

Read related article: Buffalo Dental School Featured in Netflix’s ‘Unsolved Mysteries’: Did That Head Belong to That Body?

Links to Bonwill’s Triangle

Sweeney connects this triangle to Bonwill’s Triangle—a dental concept first described in the 19th century that governs optimal jaw alignment and function. He notes that the triangular structure recurs throughout the human body and is mathematically defined by the ratio √8/3, or approximately 1.633.

“Leonardo’s drawing isn’t just a study in proportion—it’s a map of tension,” said Mac Sweeney. “The 1.633 ratio appears in the jaw, the spine and the skull. It reflects a state known as vector equilibrium, where structural tension and compression are perfectly balanced. I believe this marks the final step in the human journey toward full upright posture.”

That ratio, derived from the geometry of the cuboctahedron, is widely recognized in biomechanics and architecture as a hallmark of tensegrity—the balance of forces within a stable form. According to Mac Sweeney, this geometry defines what he calls the “Vitruvian Morphotype”: a form shaped not by aesthetic ideals but by evolutionary necessity.

“Nature solves gravity the way it solves water. Vitruvian Man is the first full sketch of what that solution looks like.”Mac Sweeney.

‘Ratio may represent evolutionary omega point’

As humans evolved to walk upright, Mac Sweeney suggests the 1.633 ratio may represent “our evolutionary omega point”—a structural threshold beyond which no further adaptation is needed to stand, move or balance efficiently in gravity.

He argues that fossil evidence should reveal a gradual convergence toward this geometric configuration, particularly in the jaw. One key moment, he notes, is the appearance of Class I occlusion—commonly known as the overbite/overjet “step”—about 8,000 years ago. While variations still exist, he believes modern Homo sapiens are the first species to fully express the Vitruvian Morphotype.

“It’s like the hydrodynamic form of a dolphin,” he said. “Nature solves gravity the way it solves water. Vitruvian Man is the first full sketch of what that solution looks like.”

Mac Sweeney suggests that da Vinci may have intuitively grasped principles of structural engineering centuries ahead of their formal articulation. This adds new weight to the drawing’s legacy, placing it at the intersection of evolutionary biology, anatomical function and mathematical design.